Why Our Planet is a Breeding Ground for Emerging Diseases

Rapid human population growth and the wide-reaching impact of climate change have contributed to a decades-long rise in new infectious diseases, say Columbia researchers.

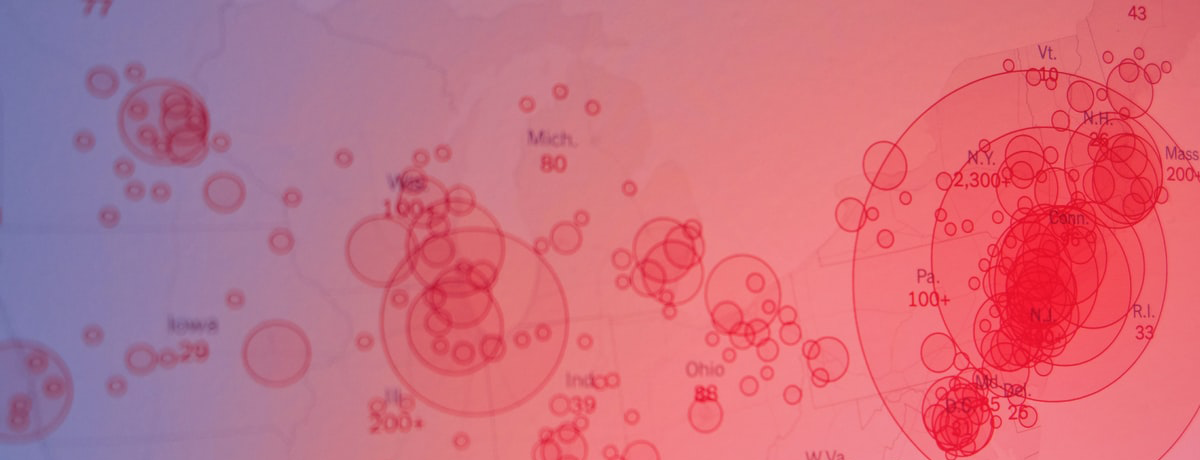

A Columbia study found in 2008, over a decade before the COVID-19 pandemic, that 335 new infectious diseases emerged between 1960 and 2004 alone. The majority of these surfacing diseases came from viruses or bacteria that spread from animals to people. The study warned such “spillover” events are happening more often.

Yet this uptick, which began in the late twentieth century, arrived after a short-lived, optimistic period post-World War II. Many public-health officials in the US then argued that infectious diseases would be problems of the past. They did not predict humans would stretch the planet’s limits, creating conditions ripe for diseases to leap from animals to people.

“As people move into previously undeveloped habitats, wild animals are being crowded into smaller areas and are mixing with people more,” says coauthor Marc Levy, a geospatial data expert at Columbia’s Earth Institute.

Many other factors are contributing to the emergence of novel diseases, says W. Ian Lipkin, professor of epidemiology and the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health. He points to climate change, which is shifting the habitats of wild animals, leading many to migrate to populated areas; and the growth of megacities in the developing world, where poor sanitation heightens people’s risk of contracting insect-borne diseases.

“In recent years, all of these elements have been in play,” said Lipkin. “It’s a perfect storm.” Learn more.

Make Your Commitment Today